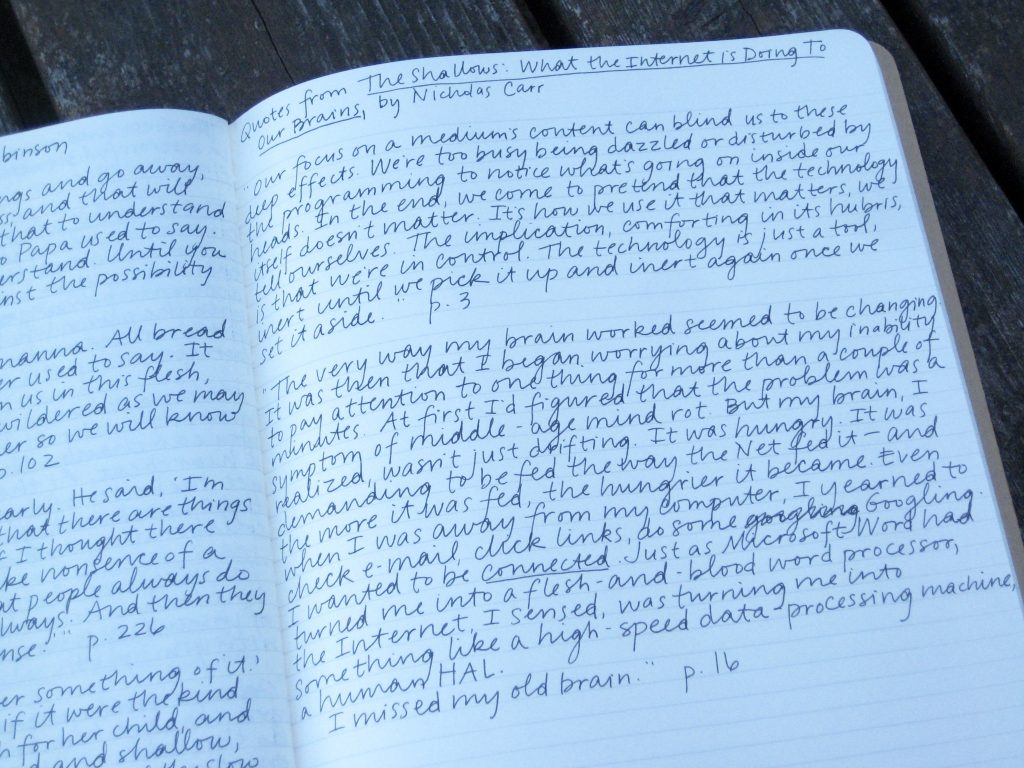

Old technologies: a pen and paper. (In this case, quotes from The Shallows that I wrote down in my personal “commonplace” book of quotes and passages.)

This is your brain on the internet.

I’m not talking about the image above; I’m talking about your brain, right now since in order to read this newsletter you have to be on the internet (sorry friends that I stopped printing hard copies years ago). And I’m talking about my brain too, as I write this. As you read this newsletter, do you have other windows open on your computer? Will you hear a notification sound during your read of this, which might draw you away for a moment to check for another important email or message? I admit that I have other tabs open, and it’s likely that I’ll pause at some point in the composing of this to look at something else. Because, well, this is how most of us function these days — multi-tasking to a high degree via our technologies.

I don’t mean to freak anyone out, and perhaps this is stating the obvious, but these new normal ways of being in the world — constantly connected, constantly interrupted, constantly multi-tasking, constantly skimming a screen for quick information — is apparently changing our brains. Or, so reports Nicholas Carr in The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains (2010).

Friends and acquaintances will know that a book with that title would interest me. I’m a slow adopter of certain technologies, still holding out against a smartphone (I’m happy to show off my sliding QWERTY keyboard if anyone is interested in seeing my old-school phone) and resisting joining some popular social media platforms (I’ve drawn the line at nothing besides Facebook). I complain about the internet a lot too, probably eliciting quiet inner eye rolls from some audiences. I find myself drawn to writers who confirm my bias against too much connection, so when I learned of Carr’s book, I was excited to read it.

I thought that I knew what he was going to say beforehand, but his book surprised me with the breadth and depth of his research and arguments. I was first surprised with finding in opening chapters the first very familiar descriptions I’ve ever read of how I feel when I spend too much time on the computer. Carr was actually an early adopter of many technologies and embraced each new development enthusiastically. He is no alarmist Luddite crying alarm at novel technologies (in fact, he addresses that response to his work throughout by putting these new technologies with the context of other historical sea changes). But, he reports that as he embraced early computer and internet technologies, he personally began to notice a profound (and unpleasant) shift in his thought patterns. He noticed that his brain seemed to be “hungry” for email and click links, even when he wasn’t around the computer. He also found that it was very hard for him to sit for long periods of time to do focused deep reading with books anymore. As he said: “I missed my old brain.”

I can relate to this experience so well, and it is why I’ve struggled with my relationship with technology my whole adult life. I totally see all the benefits and uses of all of it, which is why I’m on here typing a blog entry and why I sent a friend a series of Facebook messages earlier and why I will later stop by my Quickbooks window to make an invoice for a restaurant. However, I do not like how it all makes my brain feel. Compare these common two scenarios in my life:

- An hour spent sitting in a hammock reading a thoughtful non-fiction book (such as The Shallows)

- An hour spent clicking around doing various tasks (shopping, messaging, working) and following links on the computer

Here are my comparisons between the two: In scenario #1, time will actually feel longer than an hour. I have always enjoyed that treat of deep reading, where time slows down even though I am happy (in contrast to many happy moments in life where time seems to speed up). After the hour of reading, I will stand up, stretch, rub my eyes a bit, and feel refreshed for the rest of the afternoon. I will feel like the period of time gave me a long continuous thread of restful attention.

In scenario #2, I will feel like no time passed at all. I will likely feel like I didn’t get done what I sat down to do, because I will have been distracted so many times by incoming emails or random thoughts. After the hour, I will feel foggy and distracted and have a hard time focusing on the people or world around me. I will feel like the period of time left me with fragments of thread.

I observe the results of these two scenarios regularly, and it is why I grapple with how to best use technology so that I can benefit from it without being consumed by it. But, I find it very hard to achieve that balance, continually getting sucked in for rounds of scenario #2 without intending to. And, in Carr’s book, he talks about how there is no simple using of a tool. To use a tool, especially a technology as profound as the internet and related communication devices, changes us. It’s never a one-way relationship. Our brains are incredibly plastic and change and adapt to the ways we use them. For example, the more we engage in interrupted, multi-tasking types of technologies, the more we train our brain to be interrupted (making single focus more difficult).

Carr’s book dives even deeper, almost into the realm of philosophy, as he examines our very conceptions of what it means to be human. We’re not computers, he says, and we miss out on understand how our brains actually work if we assume that “off loading” mental work onto computers “frees up” data space. Our thought process is infinitely more complex than the binary codes that make up programing, and our ability to learn and remember are organic processes that require (drum roll) … our attention.

As a specific example, Carr cites several different studies involving reading comprehension and information retention that compared linear reading (i.e. just text, either on paper or a very plain screen presentation) versus more interactive reading experiences (screen-based with hyperlinks, images, etc.). Consistently, the linear presentations lead to greater comprehension and retention of information. Apparently, even the most minor “interruptions” in our reading process (such as whether deciding to click a hyperlink) affect our ability to learn.

So, I’ve been thinking (again!) about how and when I pay attention. How much do I multi-task? (When on the computer or in the office, a lot!) What are the practical choices I can make to lead my brain back into more experiences of that long thread of attention that evidence suggests leads to a different quality of learning (and also that I find infinitely more pleasing as a person).

I always ponder what it would be like to make even more radical choices to disconnect, beyond the limits I’ve already placed upon myself. Many times over recent years I’ve thought “We farm for a living! Surely we have a choice in how we engage technology!” But in this era, to disconnect completely feels very difficult. Because so much of life is connected, it seems like to disconnect would require dropping responsibility in many areas of life. It could lead to more peaceful days and long threads of attention, but how would we maintain farm communications with chefs and customers? How would we maintain friendships?

I recently ran across a series of columns on The Guardian website, written by a man who has decide to forgo “all” modern technologies, communication and otherwise (not sure exactly where he draws his line, but I know it excludes electrical technologies of all kinds, even off-grid ones). I couldn’t help feeling irritated by his columns, probably in large part because of jealousy, but also because it seems like such a privileged choice. He has the choice to let go of technologies that have historically and globally been liberating to women and children (hauling water and fire wood can take hours per day). But he reports feeling great peace in his technology (and responsibility?) -free days.

We’ve never gone that far. But not that long ago, we did manage to maintain all our responsibilities and relationships without internet at home at least. For the first three years of the farm, we didn’t have internet on the farm. Chefs would call on harvest days to find out what we had and place their orders. (Do our long-time customers remember calling to place your Holiday Harvest orders?) And, once or twice a week, we would get our email and internet business done using wi-fi in our “downtown office” (i.e. Red Fox Bakery). When we were on the farm, we were just here. (To put our inconvenience-comfort level in context, we also didn’t have laundry facilities on the farm yet back then either!)

Once I became pregnant with our first child in 2009, we started realizing that needed more of those conveniences at home (internet and laundry both), and life changed. I have spent the intervening years constantly brainstorming ways to engineer new limits into my life, to get back to that head space of being present.

I know I’m not alone in these struggles, although I’ve often wondered whether I am more particularly sensitive to the vagaries of my mental space than others. Quite possible. That is why reading The Shallows was refreshing to me, because I found a kindred ambivalent technology user in Carr. And, receiving affirmation that my experience is real helps me (once again) to reassess my habits. I have already turned off all notification sounds on my email and Facebook, which is a great way to begin ending the constant experience of interruption. I want to slowly adjust how I use the computer so that I don’t multi-task at all — perhaps by only having one application open at a time! It doesn’t seem like a big deal, but can you imagine actually doing that? I haven’t established that habit yet, but I’m intrigued by the possibility.

Meanwhile, in farming land, we’re in the thick of so many fall harvests out here. The sunlight has turned golden. Pears are falling on our path to our house. The nuthatches have returned to our feeders. These are things worthy of our undivided attention.

Enjoy this week’s vegetables!

Your farmers, Katie & Casey Kulla

~ ~ ~

Fall Open House ~ 2-4 pm, Saturday, October 14

Make sure you have this date on your calendar! We’ll be hosting our annual fall open house on the farm in mid-October this year. Join us for tours of the farm, an apple variety tasting, and live music from local duo Luminous Heart. I’ll post directions in the next two week’s newsletters. We hope you’ll join us!

Meet this week’s vegetables:

- Concord grapes

- Prune plums

- Jonagold apples

- Pears

- Sweet peppers

- Tomatoes

- Kale — Greens season is coming back! So many other good things abound in mid- to late summer that we often take it easy on cooking greens in the harvest round-up. But you’ll be seeing more and more of these yummy greens returning to the weekly list as we move into the season of stews and sweaters and scarves! (Which aren’t necessarily related to kale directly, but they sure are in spirit!)

- Delicata squash

- Spaghetti squash

- Pie pumpkins

- Beets

- Garlic

So true, and I couldn’t agree more! It feels like I spend so much more time on my computer and online these days, yet I am less productive in that time that ever before. So easy to fall into the hole of catching news headlines, articles on new recipes I want to try, oh wait there’s some beautiful photos of the annual bird photography contest, “ding” gotta go see who sent me a message, “ding” oh, more emails to respond do….

I’ve been on a crusade to get together with people in person much more lately, for neighborhood potluck dinners, coffee with girlfriends, and just peacefully crafting on y own, while not falling down into the hole that is Pinterest. The face-time with friends, family, and nature is so much more fulfilling and nurturing to my soul.

Love reading your weekly newsletters!