Potato in French: “Pomme de terre” … literally: “fruit of the earth” A very humble vegetable!

Did you know that the word “humility” originates from “humus,” or soil? I imagine that the tie between humility and the earth evolved as a metaphorical connection. We might also say that a person who is humble is also “grounded” or “rooted,” and I’d guess that in most cases we are talking about a grouping of related concepts rather than a person who literally has roots growing from their feet!

Without those concepts, however, humility actually can become hard to define. Humility is a trait that many people value — it is the ability to recognize one’s own limits or faults, the choice to acknowledge the needs of others and to see that the world is much larger than one’s own immediate needs/wants/existence. But those are just individual aspects of humility that help us understand a concept hard to describe without metaphors but yet so easy to identify in another human being.

Even if we think we admire traits other than humility — as so many people seem to do if we are to believe celebrity culture and the election of narcissists to office — I think that we all still recognize humility in others and find it a deeply comfortable trait to be around. I don’t mean “comfortable” in an easy, there-is-never-work-to-be-done way. But relationships with people who are humble are comfortable because we know they are people who will meet us halfway in conflict. We know that when work does arise, someone who is humble, grounded, embodying the metaphors of soil, will not be afraid or unwilling to dig into that work as well. That creates an inherent sense of trust, simply in sensing that in the people around us.

As someone who has spent a lot of time digging in the actual soil — even literally kneeling and crawling on it — the metaphors and connections between those valued human traits and the earth make sense to me. I don’t want to make the claim that I am humble (especially because, well, that’s almost an impossible assertion to make as it seems to contradict itself simply in the statement!), but I feel comfortable saying that I find working in the soil to feel humbling. I experience this humbling on at least two levels:

First, the sensual experiences of being close to the earth — face deep into plant matter, hands touching soil and leaf and stem, knees holding my weight — feels like the posture of prayer. It triggers the same feelings of connection, awe, wonder, and gratitude that I have at times also felt kneeling in prayer in church. I have to believe that the kneeling on the soil came first, and that we adopted it for worship later to pull on this deeply rooted posture and all that it evokes in us — being close to the body of the earth, our sustenance, the layers of the past that are buried below us, the bones of our ancestors, the nutrients of formerly living things, the star dust.

When I have spent a day kneeling in this way, I feel different. It’s a deep well I can tap into again and again. The feeling isn’t elation; it isn’t power; it isn’t pride. All of those feelings seem to pull a person up, and there is a place for all of them. Instead it is very much a pulling down, a reminder that I too will join the ancestors below, that I will become part of what I am kneeling upon. But that feeling comes with a sense of comfort too, because I am being held up by the earth.

Does this experience magically turn me into a better, more moral, kinder person? I wish! Certainly even with that truly humbling experience, I am a human being on a journey. But revisiting the soil and that posture work their magic on me over time, and it is safe to say that the combination of years of farming plus years of general living have changed me in ways I would call “humbling.”

Along these lines, the work itself is humbling. Please do not be mistaken — farming is skilled work. Even the most “basic” tasks such as weeding requires some level of skill. And yet, it is repetitive work. Much like the house cleaning and cooking, it is work that is never “done.” And, in our culture, such work is given lower status. It is also work that can simply feel defeating at times, knowing that even a well-weeded row today may need to be weeded again in a week or two. In spite of the skill involved, it can feel so basic, so rudimentary.

As Casey and I have acquired more skill and expertise and experience elsewhere, some days it feels odd to then spend hours simply hoeing lettuce (as we did this weekend). By society’s standards, that might not be the best use of our time if we are also capable of doing other, “more skilled” or “more critical” or better paid (or even more interesting) tasks.

And yet. This is where it all begins. There is no concert without food. There is no medicine without food. There is no legislative bill without food. There is no higher education with food. There is no culture or society without food.

To be clear, I’m not trying to put farmers on a pedestal here — that energy sometimes seems just as misguided as being dismissive of farmers. I think that all workers are important (essential even!) in our complex, modern world. But, I do want to speak to my experience of spending hours and hours of my life engaged in repetitive, physical tasks on the farm and how that has reminded me again and again where it all begins. I think it is a privilege to live my life so close to the source. I have to admit that over the years, I’ve grown a more complicated relationship with tillage-based agriculture as we practice it in western cultures (I’m just not sure it’s in any way sustainable!), but organic farming is the best way we know how to produce food at this point in time.

And, given that the majority of people through time have spent a majority of their working time engaged in procuring food, this repetitive work again ties me to ancestors going back countless generations. Tending to plants, preparing ground, planting seeds, harvesting — this is work my grandmothers a hundred generations back would recognize in some fashion. This is part of the human experience. Even if I somehow became skilled in a million other Very Important Things, this work of weeding and kneeling is still necessary. Someone needs to do it, and by doing it myself, I remind myself that all my skills — any expertise I ever gain — comes back down to this. To the sustenance of the earth and the plants and animals that share this home with us. That’s it.

To me, these are the root experiences of “humility” — or at least of being “humbled” — the metaphors made manifest. Can we live every day, all day with the awareness that I dip into when I’m deep in my work? Probably no more than it’s realistic to carry the calm of meditation into every waking minute. But, just as regular meditation or prayer can — over time — change the thoughts, emotions, and patterns of a practitioner, I think the regular visiting of the earth can change us over time too.

All this to say that I think there’s no mistake in the connection between the traits of humility and the roots of the word itself. Whether a humble person spends hours weeding or not, humility seems to require some acknowledgement of how simple our lives are … how dependent we are on the natural world and each other … how finite our existence is here.

Kneeling or bending over for hours can be painful work, and I think that many people come to humility through pain. While it can be beautiful to really know and feel our finite reality (and our infinite connections and dependences), it can also hurt. There is a part of us that does not want to give up our sense of the strong, independent, highly capable, important self. But often life provides the hard lessons we need to help us learn: sickness, accidents, loss of loved ones, failures, mistakes. Each time we’re faced with one of these hard life moments, we can choose to push away, to ignore the compost building at our feet; or, we can kneel in it, thank it for the lesson, learn, be humbled.

Easy? No. Romantic? Really, actually, no. I think to truly understand the meaning of humility (both in farming and life), one needs to move way past romance and into the reality of pain. This work is so hard that no one ever arrives. We can recognize humility in others, but we probably never really truly feel it in ourselves. Because humility comes from the trying. The trying to do the best for ourselves and others. There is no arrival. Humility comes from living in the real messy world of humanity, where the weeds we pull today will inevitably regrow next week. And we just acknowledge that (again and again) and get to work.

The world needs people willing to do this unromantic, painful, dirty work. Yet in a world where people in power have to project a brand and a cultivate an image as a basic part of communication, it seems like a big challenge for many people in levels of influence to dig in and do the work. They often don’t really have room for failure on the public stage, and that’s a hard cage to live and work within. But I don’t think it’s impossible, and I’ve been heartened to see examples of leaders working to stay grounded, to be kind, to consider the needs of others. We need those examples and that work right now.

This feels like such a critical moment in history, as the entire world needs to work together to keep humanity healthy and thriving. It’s a moment when we’re all kneeling on the earth, whether we acknowledge it or not. We are all mortal in this moment and that mortality is not something we can ignore. How do we respond? Do we turn away and ignore and build a cage of self-importance? Or, do we dig in, humble ourselves, find out what there is to learn, do the work that we might need to keep doing over and over again?

It’s not sexy. It’s not romantic. It’s not flashy. But it takes us back to our roots, recognizing where we come from and what we need to thrive.

The soil is made of our ancestors — human, animal and plant — and we will join them before too long as well. With that knowledge, how shall we live? How shall we live together? That is my question these days, as I once again go out to harvest or sow.

Enjoy this week’s vegetables.

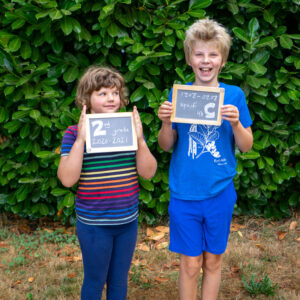

Your farmers, Katie & Casey Kulla

~ ~ ~

Payment reminder! I emailed CSA statements recently with balances due for the season. The final payment is due by this Thursday, August 27. You can bring a check or cash to pick-up; mail one to us (Oakhill Organics, P.O. Box 1698, McMinnville, OR 97128); or pay with any major credit card online here: PayPal.me/OakhillOrganics If you have questions about your balance due, you can email me: farm (at) oakhillorganics (dot) com

~ ~ ~

Meet this week’s vegetables: Wow. We really had to pare down the list this week, since All The Things are On. This is the simple version of our Very Abundant August Offerings … And salad is back in the form of beautiful frizzy frisée!